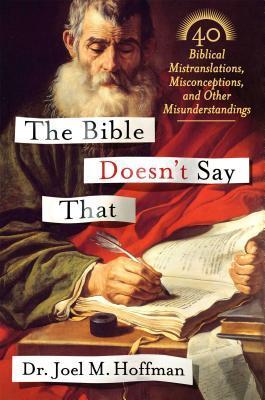

Joel Hoffman’s latest book, “The Bible Doesn’t Say That: 40 Biblical Mistranslations, Misconceptions, and Other Misunderstandings,” caught my eye soon after it was published.

I love studying and teaching Torah, and I am always on the lookout for ways to engage with biblical text from a new perspective. I mostly teach adults who consider themselves to be secular or liberal-minded Jews. Sometimes they come to Torah study with reluctance, sometimes with curiosity; more often than not, they come with a lot of preconceived notions.

I picked up Hoffman’s book because it was published in the year of one of the most contentious elections of my lifetime, with politicians slinging faith-based statements to win favor. Hoffman’s book proved to be a useful tool for wading through the misinterpretations of biblical text and an interesting read beyond the goal of staying sane during an election cycle.

Time and time again, I realize that my students’ experience of the Torah is derived from second- and third-hand perspectives. They have heard the main stories of the biblical heroes. They chanted Torah when they became b’nai mitzvah. They have been talked at by various educators about the Torah.

What many of my students have in common is that they rarely handle the book itself, and we often begin by getting comfortable with finding our way through the maze of narratives, chapters, verses and commentaries.

We open several Bibles from different publishers offering different translations, and we analyze how translation itself is an interpretation of text.

Many students ask why we, in the 21st century, are still reading and studying biblical texts that seem antiquated and irrelevant.

Jack Miles, a modern theologian who wrote “G-d: A Biography,” begins his book with the following statement: “That G-d created mankind, male and female, in his own image is a matter of faith. That our forebears strove for centuries to perfect themselves in the image of their G-d is a matter of historical fact.”

Jews and Christians have revered the Bible, a book on the all-time best-seller list for thousands of years, as the backbone of Western civilization. Regardless of whether you read it literally or as a work of literature, the Bible has permeated our culture, and the reading of it, with all of its complexities, offers a window into what it means to be human. And it is worth reading.

Hoffman, whose audience is anyone who cares about the Bible, is an academician and holds a doctorate in linguistics. What I found refreshing about “The Bible Doesn’t Say That” is that it is written in an engaging, accessible language without being condescending to lay readership, yet it holds the attention of someone who is a habitual Bible reader.

Hoffman points out five pitfalls that cause the distortion of biblical text: ignorance, historical accident, culture gaps, mistranslation and misrepresentation. He warns against untrained recitation of biases and misconceptions, offering to take the reader on a journey stripped of any agenda.

Hoffman’s most recent book tour has brought him through the heart of the Bible Belt, and he has captured the attention of Jewish and Christian audiences alike. He is careful about not being prescriptive in matters of faith, as that is not the goal of his writing.

In “The Bible Doesn’t Say That,” Hoffman’s research is not focused on the origin of the Bible, and he does not challenge its religious context. He is merely addressing the misunderstanding of some the most familiar biblical passages in an attempt to set the record straight.

For example, I appreciate Hoffman’s insight into New Testament texts, shedding light on mistaken claims of Jews’ role in the death of Jesus that fueled centuries of hatred.

The end of the book addresses what the Bible says about two of the most politically contentious issues of our time, homosexuality and abortion.

Hoffman’s analysis is that the Bible doesn’t care much about homosexuality, and its stance is “limited to rejecting male homosexual sex with the same vehemence as, for example, clothing made from wool and linen mixtures.”

As for abortion, the issue at the core is the sanctity of life. Hoffman points out that if we want to understand what the Bible says about abortion, we need to know whether a fetus is considered a person. As frustrating as it is, the Bible doesn’t give us an answer for the crucial question of when life begins.

Therefore, many of the beliefs around those two issues are based on politically driven interpretation of text and not on what the text actually says.

It is important to note that Hoffman is not suggesting that we not interpret biblical text. That would turn the text static and certainly make it irrelevant to a modern reader. I think Hoffman is attempting to sensitize the reader to common distortions of text so that we make informed choices about our understanding of the Bible.

If it seems like a daunting task, that is because it is. Perhaps that is the reason many of us will read the Torah, year after year, repeating the same passages, going over the same narratives.

Rabbi Ismar Schorsch, a former chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, wrote that “the Bible is a universal book, with a chapter for every part of human experience — lust, desire, renewal, rage, pedantry, and inexplicable suffering, a book of mourning and a book of passion and many books of pain.”

Doesn’t that sound like a book worth reading?